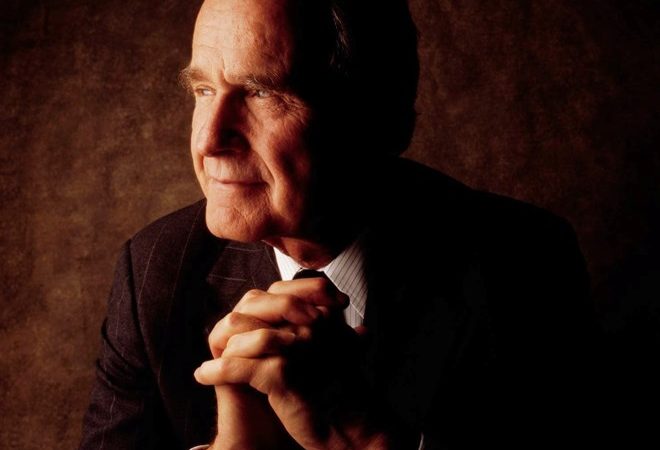

The Washington Post | December 1, 2018 | By Karen Tumulty – George H.W. Bush, the 41st president of the United States and the father of the 43rd, was a steadfast force on the international stage for decades, from his stint as an envoy to Beijing to his eight years as vice president and his one term as commander in chief from 1989 to 1993.

The last veteran of World War II to serve as president, he was a consummate public servant and a statesman who helped guide the nation and the world out of a four-decade Cold War that had carried the threat of nuclear annihilation.

His death, at 94 on Nov. 30 also marked the passing of an era.

Although Mr. Bush served as president three decades ago, his values and ethic seem centuries removed from today’s acrid political culture. His currency of personal connection was the handwritten letter — not the social media blast.

He had a competitive nature and considerable ambition that were not easy to discern under the sheen of his New England politesse and his earnest generosity. He was capable of running hard-edge political campaigns, and took the nation to war. But his principal achievements were produced at negotiating tables.

“When the word moderation becomes a dirty word, we have some soul searching to do,” he wrote a friend in 1964, after losing his first bid for elective office.

Despite his grace, Mr. Bush was an easy subject for caricature. He was an honors graduate of Yale University who was often at a loss for words in public, especially when it came to talking about himself. Though he was tested in combat when he was barely out of adolescence, he was branded “a wimp” by those who doubted whether he had essential convictions.

This paradox in the public image of Mr. Bush dogged him, as did domestic events. His lack of sure-footedness in the face of a faltering economy produced a nosedive in the soaring popularity he enjoyed after the triumph of the Persian Gulf War. In 1992, he lost his bid for a second term as president.

“It’s a mixed achievement,” said presidential historian Robert Dallek. “Circumstances and his ability to manage them did not stand up to what the electorate wanted.”

His death was announced in a tweet by Jim McGrath, his spokesman. The cause of his death was not immediately available. In 2012, he announced that he had vascular Parkinsonism, a condition that limited his mobility. His wife of 73 years, Barbara Bush, died on April 17.

The afternoon before his wife’s service, the frail, wheelchair-bound former president summoned the strength to sit for 20 minutes before her flower-laden coffin and accept condolences from some of the 6,000 people who lined up to pay their respects at St. Martin’s Episcopal Church in Houston.

Mr. Bush came to the Oval Office under the towering, sharply defined shadow of Ronald Reagan, a onetime rival for whom he had served as vice president.

No president before had arrived with his breadth of experience: decorated Navy pilot, successful oil executive, congressman, United Nations delegate, Republican Party chairman, envoy to Beijing, director of Central Intelligence.

Over the course of a single term that began on Jan. 20, 1989, Mr. Bush found himself at the helm of the world’s only remaining superpower. The Berlin Wall fell; the Soviet Union ceased to exist; the communist bloc in Eastern Europe broke up; the Cold War ended.

His firm, restrained diplomatic sense helped assure the harmony and peace with which these world-shaking events played out, one after the other.

In 1990, Mr. Bush went so far as to proclaim a “new world order” that would be “free from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice and more secure in the quest for peace — a world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice. A world where the strong respect the rights of the weak.”

Mr. Bush’s presidency was not all plowshares. He ordered an attack on Panama in 1989 to overthrow strongman Manuel Antonio Noriega. After Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in the summer of 1990, Mr. Bush put together a 30-nation coalition — backed by a U.N. mandate and including the Soviet Union and several Arab countries — that routed the Iraqi forces with unexpected ease in a ground war that lasted only 100 hours.

However, Mr. Bush decided to leave Hussein in power, setting up the worst and most fateful decision of his son’s presidency a dozen years later.

In the wake of that 1991 victory, Mr. Bush’s approval at home approached 90 percent. It seemed the country had finally achieved the catharsis it needed after Vietnam. A year-and-a-half later, only 29 percent of those polled gave Mr. Bush a favorable rating, and just 16 percent thought the country was headed in the right direction.

The conservative wing of his party would not forgive him for breaking an ill-advised and cocky pledge: “Read my lips: No new taxes.” What cost him among voters at large, however, was his inability to express a connection to and engagement with the struggles of ordinary Americans or a strategy for turning the economy around.

That he was perceived as lacking in grit was another irony in the life of Mr. Bush. His was a character that had been forged by trial. He was an exemplary story of a generation whose youth was cut short by the Great Depression and World War II.

The early years

George Herbert Walker Bush was born in Milton, Mass., on June 12, 1924. He grew up in tony Greenwich, Conn., the second of five children of Prescott Bush and the former Dorothy Walker.

His father was an Ohio native and business executive who became a Wall Street banker and a senator from Connecticut, setting a course for the next two generations of Bush men to follow. His mother, a Maine native, was the daughter of a wealthy investment banker.

Mr. Bush’s early years were hard ones for the country, although his family — which had a cook, a maid and a chauffeur — felt none of it. He attended the private Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass. The close-knit Bushes spent summers at the family house at Walker’s Point, Maine, and Christmases at his grandfather’s shooting lodge in South Carolina.

At a prep school party during the 1941 Christmas season, he spotted a girl in a red-and-green dress. He asked another boy to introduce him to Barbara Pierce, whose father was head of the McCall’s publishing empire.

“I thought he was the most beautiful creature I had ever laid eyes on. I couldn’t even breathe when he was in the room,” Barbara Bush would later say, adding, “I married the first man I ever kissed.”

Prescott Bush wanted his son to go right to Yale upon graduation from Andover. But Mr. Bush said his father had also insisted that privilege carried a responsibility to “put something back in, do something, help others.”

His own time to serve came on his 18th birthday, when he enlisted in the Navy; within a year, he received his wings and became one of the youngest pilots in the service.

Sent to the Pacific, he flew torpedo bombers off the aircraft carrier San Jacinto. On Sept. 2, 1944, his plane was hit by Japanese ground fire during a bombing run on Chichi Jima in the Bonin Islands in the western Pacific. He pressed his attack even though his plane was aflame.

Mr. Bush bailed out over the ocean and was rescued by a submarine. His two crewmen were killed. The future president was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After the war, he went to Yale, where he was a member of Skull and Bones, the university’s storied secret society, and captain of the baseball team. Barbara took their baby son, George W., to the games.

In 1948, following his graduation, he was rejected for a post he wanted with Procter & Gamble. So he moved to Texas to go into the oil business, snagging an entry-level job through a family connection.

His political career

Mr. Bush began his political career as chairman of the Harris County Republican Party at a time when being a Republican in Texas was as much an electoral liability as having Northeastern roots.

In 1964, he ran for the U.S. Senate and was defeated by Democrat Ralph Yarborough. In 1966, after selling his interest in his oil company, Mr. Bush was elected to the first of two terms in Congress from a House district in Houston.

In 1970, at the request of President Richard M. Nixon, who wanted to shore up Republican fortunes in Texas and elsewhere in the Sun Belt, he made a second run for the Senate and lost to Democrat Lloyd Bentsen.

Mr. Bush recruited his longtime friend James A. Baker III — a nominal Democrat with little interest in politics — to run that campaign, in part to help Baker get through his bereavement after the death of his wife. Baker switched parties, and their friendship became an alliance that would help shape policy and politics for decades.

After Mr. Bush’s 1970 Senate defeat, there came a rapid progression of high-profile jobs that began when Nixon named him ambassador to the United Nations. In 1973 and 1974, Mr. Bush served as chairman of the Republican National Committee during the waning days of the Watergate scandal that would result in Nixon’s resignation.

He was disappointed when Nixon’s successor, Gerald R. Ford (R), chose Nelson Rockefeller, rather than him, as vice president in 1974. In 1974 and 1975, Mr. Bush was the chief U.S. envoy to China. In early 1976, he became head of the CIA. He was well regarded but left no great mark in any of those jobs. Nor did he commit any major blunders.

After former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter (D) defeated Ford in the 1976 presidential election, Mr. Bush returned to private life and began preparing for his most audacious move yet: a run for president.

During the 1980 primaries, Mr. Bush positioned himself as a moderate, pragmatic alternative to Reagan, and he derided as “voodoo economics” the former California governor’s vow to simultaneously cut taxes, boost defense spending and balance the budget.

Mr. Bush pulled off a surprise win in the Iowa caucuses and declared he had “big mo’ ” that would carry him to the nomination. Ultimately, he proved no match for Reagan and the conservative forces that had come to dominate the party.

Yet he found another opening at the Republican National Convention that year, when he emerged as the consensus choice to be Reagan’s running mate, after party elders botched an effort to put together a Reagan-Ford ticket.

It took no small amount of adjustment for Mr. Bush to remold himself according to Reagan’s brand of conservatism. Among other things, he changed to Reagan’s positions on abortion and supply-side economics. The cartoon “Doonesbury” later described him as having put “his political manhood in a blind trust.”

The ticket won in back-to-back landslides in 1980 and 1984. Once elected, Mr. Bush maintained a relatively low-profile role as vice president — chairing a number of task forces, offering counsel on foreign policy — while sharpening his bona fides and his political organization to make another run for the presidency.

Mr. Bush was barely brushed by Iran-contra, the major scandal of the Reagan presidency. He said he had been “out of the loop” when decisions were made to sell military equipment to Tehran to gain the release of U.S. citizens held hostage by pro-Iranian terrorists in Lebanon. This was contrary to Reagan’s declared policy of never dealing with terrorists. The profits from the sales were used to provide aid to the anti-communist contra rebels in Nicaragua, which was a violation of U.S. law.

Never fully accepted into the Reagan inner circle, Mr. Bush established some distance from his former boss in his 1988 Republican National Convention speech, when he promised a “kinder, gentler nation.” Reagan’s wife, Nancy, was widely reported to have bristled, asking: “Kinder and gentler than whom?”

In the 1988 election, Mr. Bush’s Democratic opponent was Massachusetts Gov. Michael S. Dukakis, who captured his party’s nomination largely on the strength of the “Massachusetts Miracle,” a surge of technology-driven economic growth.

The Bush campaign turned Dukakis into an object of scorn, raising questions about his patriotism, his competence, his environmental and fiscal records and, most damaging, his attitude toward criminals.

Dukakis had supported a program that allowed convicted murderers in Massachusetts prisons to earn furloughs for good behavior. One who did so was Willie Horton, who, while on furlough, went to Maryland and raped a woman after beating and knifing her fiance. Dukakis was appalled and promptly shut the program down.

To Lee Atwater, Mr. Bush’s chief campaign adviser, Horton was an irresistible opportunity. Horton was black, and his elevation into a national figure by Bush supporters was widely denounced as a crude appeal to racism. Atwater himself expressed regrets about the 1988 campaign before he died of cancer, at 40, in 1991.

Mr. Bush won the election with 53 percent of the vote. He carried 40 states and received 426 electoral votes. He was the first sitting vice president elected to the nation’s highest office since Martin Van Buren succeeded Andrew Jackson in 1837.

‘The vision thing’

As president, Mr. Bush worked long hours and had a penchant for detail. Fred Malek, his campaign manager in 1992, described him as “a guy who wanted to do everything well.” But in stark contrast to his predecessor, Mr. Bush failed to articulate an overarching view of the principles by which he governed.

“The vision thing,” as he called it, eluded him. “Some wanted me to deliver fireside chats to explain things, as Franklin D. Roosevelt had done,” he confided to his diary. “I am not good at that.” He was, he said, a “practical man,” who preferred “what’s real,” not “the airy and abstract.”

Mr. Bush espoused generally conservative economic and social programs: lower taxes, regulatory reform, more support for commercial development and access to foreign markets. He negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico, a measure that was ratified by the Senate in President Bill Clinton’s first term.

Mr. Bush supported voluntary prayer in public schools and adoption rather than abortion. He also supported gun owners’ rights. “Let’s not take away the guns from innocent citizens,” he said in a speech. “Let’s get tougher on the criminals.”

Faced with Democratic control of both houses of Congress, Mr. Bush followed what became known as his “veto strategy.” In all, he vetoed 44 bills. Ten of them were intended to ease restrictions on abortions. The others concerned various regulatory, tax and spending measures. All but one of his vetoes — of a bill to regulate the cable television industry — were sustained.

But Mr. Bush could not allay suspicions in some quarters that he lacked core beliefs. To critics, particularly in the right wing of the GOP, he seemed willing to say whatever was necessary to get elected.

His was a team of seasoned advisers who forged an active but pragmatic foreign policy and set a less divisive and less ideological course on domestic matters.

Mr. Bush placed a high value on loyalty and on cultivating relationships that became part of the through line of his career.

Chief among them was Baker, who at various points served as Mr. Bush’s campaign manager, secretary of state and White House chief of staff. Baker also did stints as Reagan’s chief of staff and treasury secretary, and in the messy aftermath of the 2000 presidential election, led the Republican team monitoring the Florida recount that put Mr. Bush’s eldest son, George W. Bush, over the finish line.

Other relationships would also link the two Bush presidencies. After his first choice for defense secretary, Sen. John G. Tower (R-Tex.), failed to be confirmed by the Senate, Mr. Bush tapped another old friend, Richard B. Cheney, a conservative Republican congressman from Wyoming, for the job. For chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he picked Gen. Colin L. Powell, who had been national security adviser in the Reagan White House.

Baker, Cheney and Powell played central roles in U.S. interventions in Panama and the Persian Gulf during Mr. Bush’s presidency. Cheney and Powell went on to hold high office in George W. Bush’s administration: Cheney as vice president and Powell as secretary of state.

One of Mr. Bush’s more impulsive selections was his choice of Dan Quayle, the junior senator from Indiana, to be his running mate in 1988. Mr. Bush made the move without consulting even his closest aides, leaving his campaign unprepared for what followed.

There were immediate questions about Quayle’s service in the Indiana National Guard during the Vietnam War. He also attended law school at Indiana University during that period. Critics noted that he had never practiced law and suggested that he had used the Guard to avoid the draft.

Quayle never fully laid to rest those questions or the broader doubts about his qualifications for stepping into the presidency. While the vice president earned high marks as the administration’s emissary to conservatives, Mr. Bush wrote in his diary that he “blew” the decision on Quayle in 1988. But in 1992, he refused to replace him on the ticket.

Mr. Bush made two nominations to the Supreme Court. The first was David H. Souter, a federal appeals court judge, who was confirmed without difficulty. The second was Clarence Thomas, an African American who was a member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

Thomas was appointed to succeed Thurgood Marshall, the first African American to serve on the high court. Anita Hill, a former aide to Thomas, accused him of sexual harassment. After rancorous hearings by the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991, the full Senate confirmed him by a vote of 52 to 48, the closest margin since the 19th century.

Foreign policy work

It is not possible to appreciate the signature foreign policy achievements that occurred on Mr. Bush’s watch without viewing them in the context of the four decades that preceded them.

In the era after World War II, the United States sought to contain Soviet influence around the world. The nation fought divisive and demoralizing wars in Korea and Vietnam, headed the NATO alliance that stood against Warsaw Pact forces in Europe and engaged in a global nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union that infused the era with existential dread.

Within a year of Mr. Bush’s inauguration, the international situation changed almost beyond recognition. What Reagan had called “the evil empire” was collapsing, and the Soviet Union was lurching toward dissolution.

Mr. Bush approached the changing world with a view that was pragmatic rather than ideological. He had little faith in the so-called Star Wars anti-ballistic missile system that Reagan believed would protect the nation from nuclear attack, so he signed two nuclear disarmament agreements with Moscow.

As Reagan had, Mr. Bush saw an ally and a kindred spirit in Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the leader who tried to reform the Soviet system through “glasnost” (openness) and “perestroika” (economic reform). Mr. Bush said that he “could sit down and just talk. I thought I had a feel for his heartbeat. Openness and candor replaced the automatic suspicions of the past.”

In June 1989, Gorbachev announced that he would not enforce the Brezhnev Doctrine, under which Moscow reserved the right to intervene in satellite countries. Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia were escaping Soviet domination; the Baltic states were moving toward independence. Hungary opened its frontier with Austria. Thousands of East Germans used this route to defect to the West.

On Nov. 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall, a symbol of communist oppression, was breached. East Germany collapsed. Two years later, the Soviet Union voted itself out of existence.

Mr. Bush played a quiet role as Gorbachev and Chancellor Helmut Kohl of West Germany settled terms for the reunification of Germany. The deal was sealed when Kohl agreed to pay billions of dollars to shore up the Soviet economy and cover the cost of removing Soviet forces.

Mr. Bush helped convince Kohl that a reunited Germany should stay in NATO. Similarly, he agreed with French President François Mitterrand that German reunification was a matter for the Germans to decide and that only a “united Europe” could keep Germany in check. Prodded by former president Nixon, Mr. Bush gave economic aid to Moscow.

He was always mindful of Russian sensibilities. When the Berlin Wall came down, he told reporters that he did not “think any single event is the end of what you might call the Iron Curtain.”

Mr. Bush also put a high premium on stability, as evidenced by his measured — critics said inadequate — reaction to the Chinese crackdown on demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in June 1989. He suspended military sales and contacts with China but sent national security adviser Brent Scowcroft and Lawrence Eagleburger, the undersecretary of state, to Beijing to discuss the situation with Chinese leaders.

“What I certainly did not want to do was completely break the relationship we had worked so hard to build since 1972,” when Nixon opened relations with China, Mr. Bush wrote in his memoirs. “We had to remain involved, engaged with the Chinese government, if we were to have any influence or leverage to work for restraint and cooperation. While angry rhetoric might be temporarily satisfying to some, I believed it would deeply hurt our efforts in the long term.”

In Latin America, Mr. Bush ended U.S. support for the contra guerrillas in Nicaragua. In exchange for economic aid, the leftist Sandinista government agreed to free elections. A year later, the Sandinistas were voted out of power.

Reagan’s preoccupation with communism in Central America had been a major factor in the Iran-contra scandal. As Mr. Bush left office, he issued pardons for Caspar W. Weinberger, Reagan’s secretary of defense, and five other officials who had faced charges for their Iran-contra roles.

Invading Panama

Although he had an affinity for diplomacy, Mr. Bush’s legacy will also be defined by his decisions to go to war.

In Panama, Noriega had once been a valued anti-communist asset of the United States, and for several years he was on the CIA payroll. As his power grew, he enriched himself at the expense of the Panamanian public, and he became a kingpin in the drug trade. In 1988, he was indicted on drug charges by a U.S. grand jury.

On May 7, 1989, Noriega overturned an election in which his slate was defeated. Three days later, the opposition staged a protest.

The Bush administration moved to protect the Panama Canal and U.S. civilian and military personnel living in the canal zone. In October, a Panamanian major staged an anti-Noriega coup. It was immediately suppressed. Tensions between the United States and Panama escalated, as U.S. forces in the canal zone were beefed up.

On Dec. 16, 1989, one day after Panama passed a resolution saying a state of war existed between the two countries, a U.S. Marine officer was killed by Panama Defense Force troops as he and three other officers drove away from a PDF roadblock. A Navy officer and his wife who witnessed the incident were taken into custody, interrogated and threatened with death before being released.

On Dec. 17, 1989, Mr. Bush ordered U.S. forces to invade. The action began Dec. 20 with air attacks and a spectacular nighttime parachute assault.

The fighting was over in a matter of hours. On Christmas Eve, Noriega took refuge in the residence of the papal nuncio, where he remained for 10 days, during which time U.S. forces surrounded the Vatican Embassy and blasted it with ultra-loud rock music. Noriega surrendered Jan. 3, 1990. He was flown to Miami, tried and convicted of an array of drug offenses.

Desert Storm

Mr. Bush met his greatest international challenge in the Persian Gulf, where U.S. policy was driven by an insatiable need for oil. In 1990, about a quarter of U.S. oil imports came from the gulf states. A quarter of that total came from Iraq.

With stability in the region a paramount concern, Iran was regarded as the primary threat to U.S. interests after the revolution that overthrew the shah and brought the Ayatollah Khomeini to power in the late 1970s. The United States turned to Iraq as a counterweight to Tehran and supported it throughout an eight-year war with Iran.

The Bush administration continued the pro-Iraqi policy, and in 1989 the United States provided $500 million in agricultural credits to the Baghdad regime, with plans for more. The aid continued despite increasingly hostile statements directed toward Israel by Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi dictator.

Hussein had long coveted Kuwait, Iraq’s tiny neighbor to the south, which held 10 percent of the world’s known oil reserves. In the summer of 1990, Hussein massed troops on the Kuwaiti border, and in August he invaded.

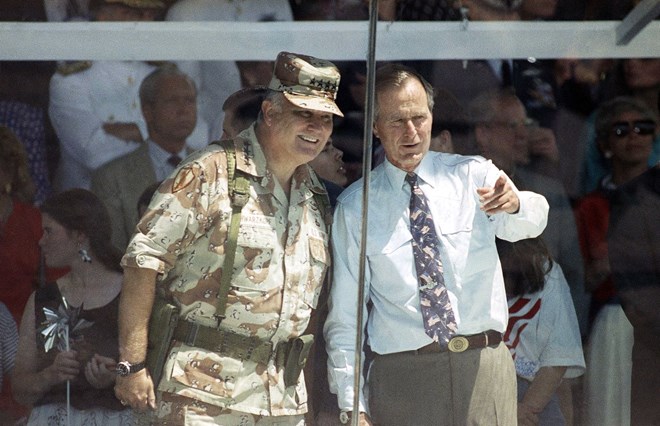

The United States was caught by surprise, but the response of the Bush administration was quick. Comparing Hussein to Hitler, the president vowed that the invasion would not stand. Working the telephones and relying on his personal contacts, he organized the 30-nation Desert Shield coalition.

He obtained a mandate from the United Nations and another from a divided Congress that was haunted by the role it had played in getting the United States into Vietnam. The resolution supporting the war passed the Senate by five votes, with all but 10 Democrats voting against it. Israel was persuaded to stay on the sidelines for fear of offending the Arabs.

On Jan. 17, 1991, U.S. and allied planes struck Iraqi targets, and Desert Shield became Desert Storm.

The ground war commenced Feb. 24, and Iraqi forces were quickly routed. Mr. Bush ordered a cease-fire 100 hours after the fighting began. He had the support of Cheney, the defense secretary; Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, the allied commander; and Powell, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

Iraq agreed not to develop nuclear, chemical and biological weapons, and U.N. inspectors were to monitor compliance. Schwarzkopf let the Iraqis keep their armed helicopters.

In the eyes of the American public and its military, the seemingly effortless victory marked the turning of a page from the national mortification endured in Vietnam.

But Hussein remained in power. He still had at his disposal the formidable Republican Guard, which had not been involved in the fighting. When Shiite Muslims in southern Iraq and Kurds in the north revolted, the guard used the helicopters to crush them.

The fighting had scarcely ended when Mr. Bush came under criticism for not pushing on to Baghdad and deposing Hussein. It was also said that he had urged the Iraqis to revolt and then abandoned the Shiites and the Kurds to a brutal fate.

The president’s answer was that the U.N. mandate called for expelling Iraq from Kuwait, not for invading Iraq or eliminating Hussein.

“Trying to eliminate Saddam, extending the ground war into an occupation of Iraq,” Mr. Bush wrote in his memoirs, “would have violated our guideline about not changing objectives in midstream, engaging in ‘mission creep,’ and would have incurred incalculable human and political costs.”

Ultimately, it was Mr. Bush’s son who achieved Hussein’s removal from power, with a war that he launched in 2003, on what turned out to be inaccurate information that the Iraqi dictator had weapons of mass destruction.

The second Iraq conflict was part of what the younger Bush called the “war on terror,” launched in the wake of attacks on New York and the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001. It led to prolonged military engagements in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Foreign policy experts say the effort had the unintended consequence of further destabilizing the Muslim world, leading to the growth of new terrorist movements.

Mr. Bush bristled at the often-made suggestion that one of his son’s motivations was taking care of the family’s unfinished business. The elder Mr. Bush told Time magazine in 2003 that whether to go to war is a lonely call for any commander in chief: “It is the toughest decision a president has to make, to send the sons and daughters of Americans into harm’s way.”

The Gulf War was not the end of Mr. Bush’s foreign policy legacy. He subsequently sponsored talks in Madrid between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization that formed the basis of a decade-long effort to forge peace in the Middle East. In his last days in office, he ordered U.S. troops to Somalia, an African country in political chaos, to deal with devastating famine.

‘No new taxes’

As the 1992 presidential election approached, the attention of the American public was turning homeward, and Mr. Bush’s political standing came crashing to earth. Eighteen months after his triumph in Iraq, his approval rating plummeted, and only 16 percent of those polled thought that the country was headed in the right direction.

Mr. Bush had promised a “kinder, gentler” America. He signed into law the Americans With Disabilities Act, a broad civil rights measure that prohibited discrimination in employment, public services and public accommodations on the basis of physical or mental disability. Among his other accomplishments were far-reaching amendments to the Clean Air Act that had been stalled in Congress for years.

But he also was confronted with threats on the economic front, one of which was a menacing budget deficit, which grew from the Reagan years and clouded every aspect of the Bush presidency, domestic and foreign. The president acknowledged as much in his inaugural address when he told the nation, “We have more will than wallet.”

Another major economic problem inherited from the Reagan era was a savings-and-loan industry crisis, which threatened the stability of the banking system. (It was also a source of embarrassment to the president because of his son Neil’s connection to a Denver S&L that failed.) Mr. Bush quickly organized a rescue package.

The deficit proved a greater challenge. Holding the line on taxes was a basic tenet of the conservative wing of the Republican Party, and Mr. Bush made it the centerpiece of his 1988 campaign. Although he feared that it might tie his hands as president, he made a pledge to cheering delegates at the GOP nominating convention:

“The Congress will push me to raise taxes, and I’ll say no, and they’ll push, and I’ll say no, and they’ll push again. All I can say to them is: Read my lips. No new taxes.”

But the nation’s accounts continued to hemorrhage red ink, and Mr. Bush decided he had to act. In 1990, he made a budget deal with the Democratic-controlled Congress, which raised taxes.

When he ran for reelection in 1992, Mr. Bush said the 1990 budget had been “a mistake,” but the damage was done. Conservatives never forgave him.

Meanwhile, as recession ravaged the economy, the president’s efforts to connect with the struggles of average Americans came off as hollow and sometimes laughable. During the Christmas season of 1991, his White House staged an infamous photo op of the president buying four pairs of socks at J.C. Penney and exhorting Americans to shop their way out of bad times. At one point, he told a town hall meeting in hard-hit New Hampshire: “Message: I care.”

In November 1992, Mr. Bush was defeated by a relative newcomer to the national scene, then-Gov. Bill Clinton of Arkansas, whose campaign took as its major theme, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

In a three-way race that included independent candidate H. Ross Perot, Clinton received 43 percent of the vote, to Mr. Bush’s 38 percent and Perot’s 19 percent.

Eight years after Mr. Bush moved out of the White House, however, he and Clinton were on a platform together at a presidential inauguration at the U.S. Capitol — this time at the swearing-in of Mr. Bush’s eldest son, George Walker Bush, as Clinton’s successor.

Only once before had the offspring of a president been so elevated, when John Quincy Adams, the son of John Adams, took office in 1825.

The inauguration of the younger Bush was a triumphant and moving occasion for members of one of the nation’s most prominent political families. Mr. Bush’s second son, Jeb Bush, served as governor of Florida from 1999 to 2007.

Jeb Bush was considered an early front-runner for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination. He lost to New York billionaire Donald Trump, who then defeated another dynastic candidate, Democratic nominee and former first lady Hillary Clinton, to be elected the nation’s 45th president. The elder Bush did not publicly support Trump and was reported to have voted for Clinton. A spokesman declined to confirm those reports, saying that Mr. Bush’s ballot was a private matter.

His private side

In 1988, Mr. Bush gave a list of the qualities he most cherished to Peggy Noonan, who wrote his speech accepting that year’s Republican presidential nomination. They were: “family, kids, grandkids, love, decency, honor, pride, tolerance, hope, kindness, loyalty, freedom, caring, heart, faith, service to country, fair (fair play), strength, healing, excellence.”

Mr. Bush viewed his family as part of his legacy. He was intensely proud of the sons who followed him into public service.

One of his greatest assets was his earthy and blunt first lady. Barbara Bush’s openness and wit made good copy for the media. Answering a question about her matronly appearance, she said, “My mail tells me a lot of fat, white-haired, wrinkled ladies are tickled pink.”

Mr. Bush enjoyed the perquisites of the presidency: Marine helicopters and Air Force One, Camp David, the Oval Office with its view of the Rose Garden in summer and blazing logs in the fireplace in winter.

He was also a hunter, fisherman and dedicated jogger, who was known to run between holes on the golf course for extra exercise. He loved barbecue, horseshoes and country music. He told reporters that he had never liked broccoli and that because he was president, he did not have to eat it.

Colleagues often commented on his charm and natural decorum. A friend remarked that as vice president, he had conducted himself with a “deferential Episcopalian tilt.”

He possessed a legendary Rolodex and called aides and colleagues at all hours of the day and night. He wrote thousands of notes to world leaders, friends, reporters and ordinary citizens.

The Bushes had six children. In addition to George W. Bush and Jeb Bush, their offspring included Neil Bush, Marvin Bush and Dorothy Bush Koch.

A daughter, Pauline Robinson “Robin” Bush, died of leukemia in 1953, two months before her 4th birthday. Her parents considered her death the greatest sorrow they ever experienced.

“There was about her a certain softness,” Mr. Bush wrote to his mother. “Her peace made me feel strong, and so very important. . . . But she is still with us. We need her and yet we have her. We can’t touch her, and yet we can feel her.”

In the years after the White House, Mr. Bush wrote his memoirs and divided his time between Houston and the family compound in Kennebunkport, Maine, where he was a vestryman of St. Ann’s Episcopal Church. He chose College Station, the home of Texas A&M University, as the site of the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum.

After the earthquake and tsunami that devastated African and Asian nations in 2005, Mr. Bush collaborated with Bill Clinton, his former adversary, to lead private relief efforts that raised nearly $2 billion in the United States.

So close did the unlikely friendship of the 41st and 42nd presidents become, that the 43rd joked: “My mother calls him my fourth brother.”

In 1997, Mr. Bush made a parachute jump for the first time since bailing out over the Pacific. He did it again in 2000 to mark his 75th birthday — and still again for his 80th, 85th and 90th ones.

“Old guys can do neat things,” he said.

.

.

J.Y. Smith, a former Washington Post staff writer who died in 2006, contributed to this report.

.

.

.

Xafiiska Wararka Qaranimo Online | Muqdisho

_________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________Xafiiska Wararka Qaranimo Online | Mogadishu, Somalia

_____________________________________________________________________________________Advertisement

_____________________________________________________________________________________