Muqdisho,2 March 2016: Ilhan Omar, 33, is a Somali-American refugee, and she’s running to be a state representative in Minnesota. She was 14 years old when she began taking her Somali grandfather to state caucuses, acting as his translator. After earning her degree in political science and international studies at North Dakota State University, she’s worked in local politics for the past 10 years.

In 2014, she was physically attacked by eight men while serving as the Vice Chair for her senate district at a Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party caucus, after she says she tried to enforce caucus voting rules. Despite that, she’s returning to caucus this year as a candidate, running to represent Minneapolis House District 60B. If she’s elected, she may be the first Somali-American Muslim woman to be elected to public office.

Omar spoke to us on the eve of Super Tuesday about being a woman of color in politics, about what she wants to do for her community, and returning to politics after being attacked. The following has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Being attacked wasn’t a deterrent for me. I don’t think I looked at it as a thing where I needed to step back or distance myself from this process. Every single election cycle I make a request of people who have dealt with this system that has been oppressive for a lot of minority communities for over 100 years: I ask them to believe in the system and to work and make the effort in changing it, because things are changeable in this country. Our democracy allows us to be active and to be full participants and to make the process work for us. And so for me to say that because this one thing happened to me that I am going to step back is sort of doing disservice and being hypocritical. And that wasn’t something I was interested in.

And so I started sobbing and I knew that no matter how much pain I was in and that fact that I suffered a concussion and could barely remember my name that I needed to go to work the next day—for the people who were involved in this process, who worked with me at city hall. I was very adamant that I went to work and I sat in the committees and made sure that they saw me and that they knew that they couldn’t silence me, and that I was stronger than they think I am.

Ilhan Omar

Ilhan Omar with her sister Sahra and father Nur.

My family came from Somalia and left when I was eight because of civil war and I grew up in a refugee camp in Mombassa, Kenya, for about four years. We arrived in the United States when I was 12.

We first arrived in Arlington, Virginia in 1995—that’s where I went to middle school. When we came I didn’t speak any English. I knew three words, and the three words were “hello” and “shut up.” It was the first time, coming from Africa, that I realized that I was black, and that my Muslim identity was a thing, and that this is the first time I realized the stigma that I carried as an immigrant and a refugee and a Muslim person who was visibly Muslim, with a headscarf. And that my blackness was a source of tension.

Dad decided that we were going to move to Minnesota because Minnesota at the time was number one in the nation with regards to education, and there was going to be economic security and the Minnesota “nice” of having welcoming neighbors. And we found that here.

Both my dad and my grandfather who helped raise me were born during colonial times in Somalia. They were always excited about this ideal of living in a democratic country, and that wasn’t available to them in their own country. So when we came to America and when we came to Minnesota, my grandfather was really excited about this tangible process that you can partake in and that you don’t have to be part of an elite to participate in. So I started taking my grandfather to our local caucuses at the age of 14, where I would be his language and cultural translator. I really fell in love with this idea of having neighbors come together and make decisions in a very grassroots level, and create resolutions, and vote for the person who is going to carry the name of their party in the next election cycle. That was really exciting for me. I got to see and believe in politics being a catalyst for making change in our daily lives.

Ilhan Omar

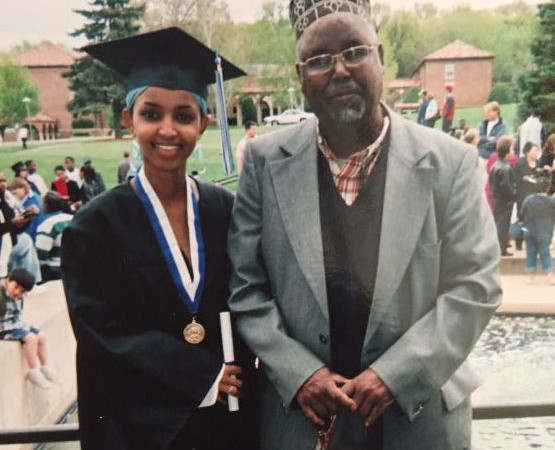

Ilhan Omar with her grandfather, Baba Abukar, at her college graduation.

My grandfather passed away recently. Him and I had that particular connection, constantly having conversations about politics. And he actually joked when I told him I was going to study political science. He said, “This is something we just do, not something we study.” We’re political and politics is in us, so you just do it, he would say.

I think when we think about representative democracy we also need to think about reflective democracy, where you see yourself as part of the governing body, right? Where seeing people who speak to your issues, people who look like you, people who come from your communities, people who understand your issues from a level of living through your experiences, becomes really important in shifting conversations. As they say, if you are not at the table, you’re on the menu.

In Minnesota, we’re number one on every list but we’re also on the bottom of every list when it comes to racial disparities, they are so high. We need to commit ourselves to eliminating racial disparities in an effort to create a prosperous and equitable Minnesota where every person benefits. We need to make sure we’re electing people who are bold in that and who will unapologetically address these issues of building an economy that supports everyone. Closing the opportunity gap, advancing equity for all, really being intentional about protecting our environment.

I think the idea of having someone like me run and possibly win allows other folks who are afraid to put themselves out there to take the leap, and to lean in, and to be the change that they want to see, and be a little braver in that process.

We live in one of the most progressive, liberal districts, so I think it’s more of just making sure that I would still champion progressive ideals and people wanting to make sure that I would be the kind of representative that they want me to be. We don’t have a lot of Islamophobia within our district. It’s more subtle and nuanced than it is on the national stage.

I still have my grandfather’s number saved in my phone. And every once in a while, when I come from a meet and greet, and you know, sometimes there are questions that are challenging or questions that are strange. I think to call him, and I dial his number and it says, “the number you have dialed is not active anymore.” And I just laugh in the car because he’s the first person I want to call. I think he would be proud but also would remind me of how much weight and pressure that carries and that I am responsible in making sure that I safeguard the reputation that comes with that.

Source: Fusion.net

Xafiiska Wararka Qaranimo Online | Mogadishu, Somalia

_____________________________________________________________________________________Advertisement

_____________________________________________________________________________________